What is a Monolith

Posted on May 31, 2020 | 8 minute read | Share viaI have worked on a large number of projects of all different shapes and sizes. Since I have worked on many existing code bases a common question I will be asked is: “can we break down our monolith”. I have been thinking a lot about this lately - in part because I see more and more frequently that leaders are attempting to approach building a micro-service as the stated outcome - and I myself feel that that is a horrible reason to attempt to build microservice. My reaction is to remind leaders that microservices are expensive - they bring a lot of really good attributes - but just stating that you want a microservice without knowing if there are any pros may not lead you where you want to go. The reality is that microservices are distributed systems and to build microservices robustly takes time and energy to think through an entirely new class of problems:

- Deployment models

- Backwards compatibility between components

- Test Strategies

- Network failure modes

- Physical Deployment methods (and associated latencies)

- Network data protection schemes

- Service Discoverability (and at scale).

- …

To balance all of this we can look to what microservices are really good at:

- Team independence

- Single Responsibility and ability to reason about success of any individual service

- Potential for better horizontal scalability

- Faster time to market

- Isolated changes

- …

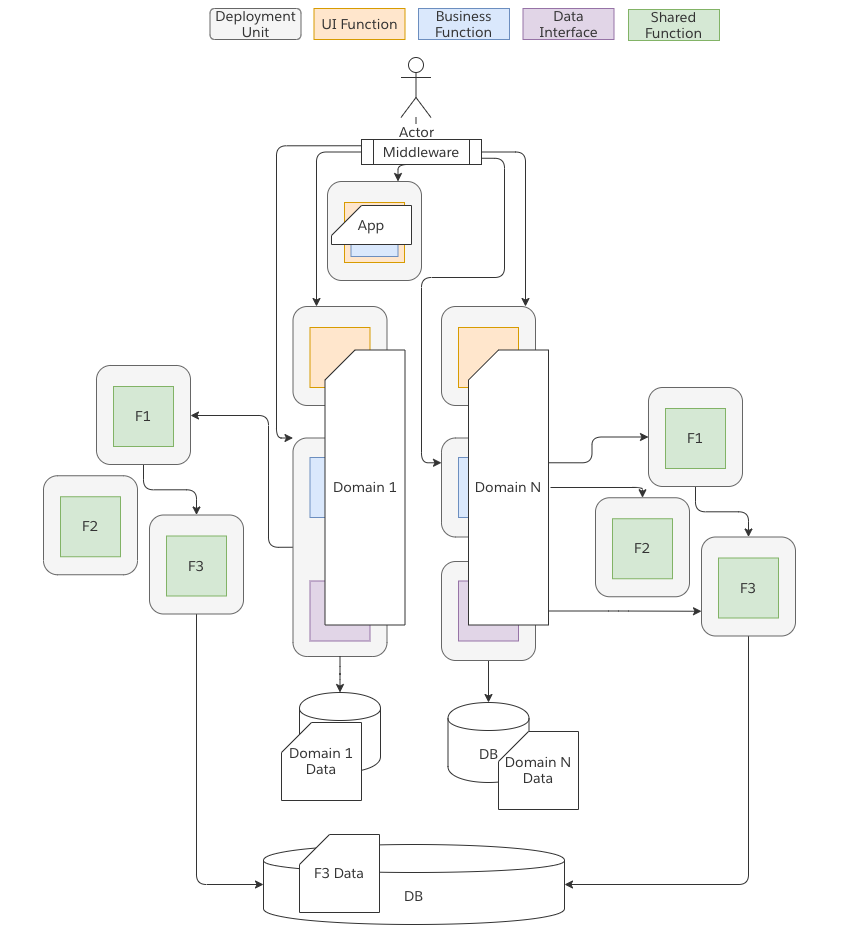

When I started to go through this list I have started to realize that in fact the conversation is less about microservice or monolith but more how things are isolated and deployed. In other words, if I can package and deploy a function and get all of the same advantages as microservices then have I achieved many of the same goals? To this end I would actually like to start to reframe the conversation to define some more specific architectural categories. This would break things down into a few key terms

- Monolith : Any system constructed as 1 or more deployable artifacts where the set of artifacts must be tested and/or deployed in any orchestrated manor. Monoliths are NOT a description of size and may be small or large in structure.

- Distributed : Any system constructed of more than 1 deployed artifact encapsulating Business Functionality.

- Domain Oriented : A system where logic is organized into independent modules of functionality and only accessed via well defined interfaces.

- Modular : Any system where each Domain Component maintains an independent set of data structures that are not shared with any other Domain Component.

From this we can begin to construct a number of different architectures

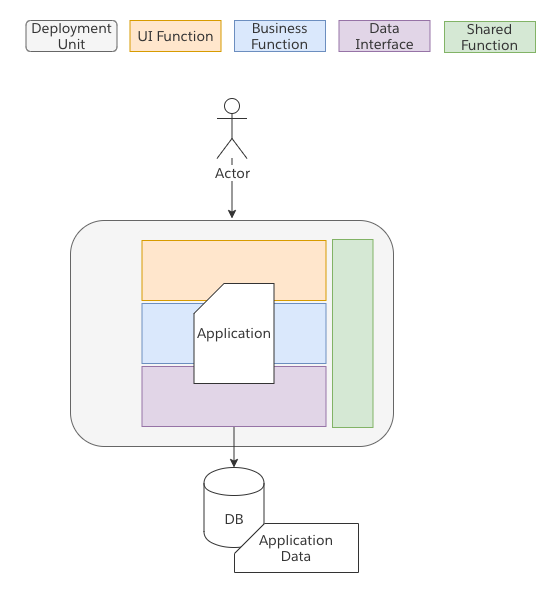

Monolithic Application

Most are likely familiar with this pattern. A Monolith is a set of logic within an executable. The logic may be arranged internally in many different ways (functional, OO, procedural, etc). While there may be “objects” those objects may not encapsulate different Domains of interested but rather the logic is oriented and optimized in support of the Application that is being built.

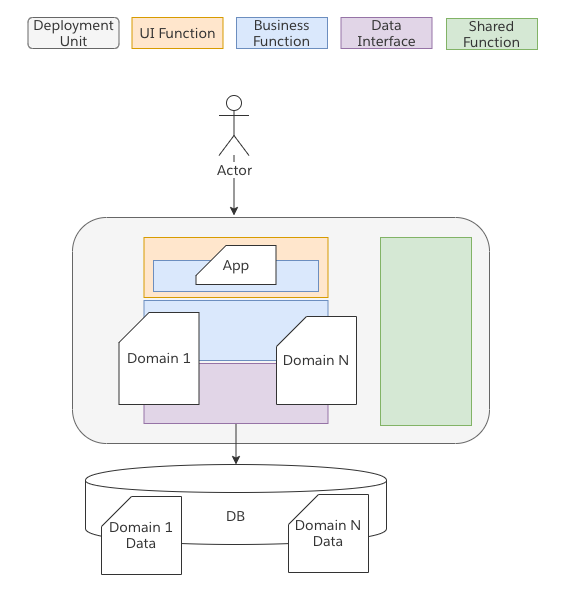

Domain Oriented Monolith

Sometimes our single application grows up and we start to support multiple different applications. At this point we may attempt to move logic around into some form of independent domains. Object Oriented programming attempts to define one such method of doing this with the intent that underlying domains may be re-used to build 1 or more different applications. While on paper such an architecture looks reasonable in practice I have found few architectures that are this clean. This is largely due to the fact that the languages on which we build simply are not great an providing such clean lines of separation and the incentives for developers make it to easy to cross such domain boundaries. As a result in practice such architectures often lead back to a “ball of mud” (or growing Monolith).

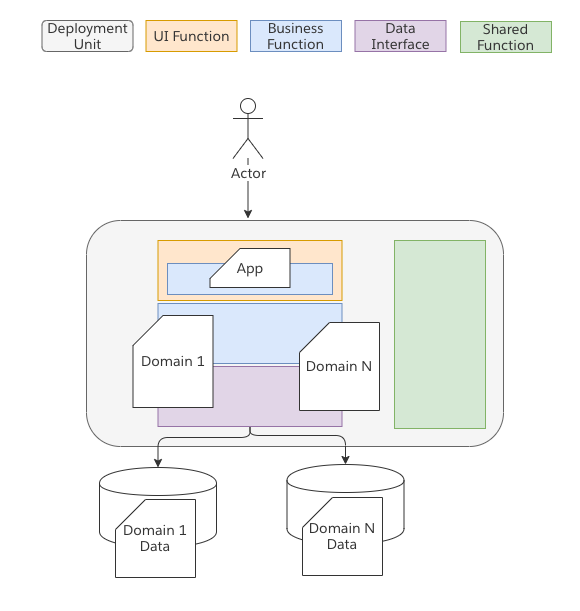

Modular Monolith

A modular monolith is a step beyond the Domain Oriented Monolith. Here we start to create slightly more firm boundaries; specifically at the data layer. Here we enforce that a Domain may only interact with the data that it owns. Within the process that is deployed there may still not be firm walls, but the friction is higher as different pieces of code can no longer simply go around a piece of logic and peak behind the covers at the data it holds. Modular monoliths are of specific interest to me as discussed at the end of this article because as K8 and other PaaS layers increase their abstractions and languages like Java start to provide stronger methods to modularize code there is a blurring line and a more subtle set of trade-offs.

For many larger Monoliths that exist today I think that starting by thinking about build a Modular Monolith may be a great first step to begin to create more modular chunks of code that could be split into independently deployed microservices. It also forces solving one of the more difficult concerns when moving to microservices up front which is how to denormalize data and then begin to create materialized views of information where the logic lives and requires for consumption.

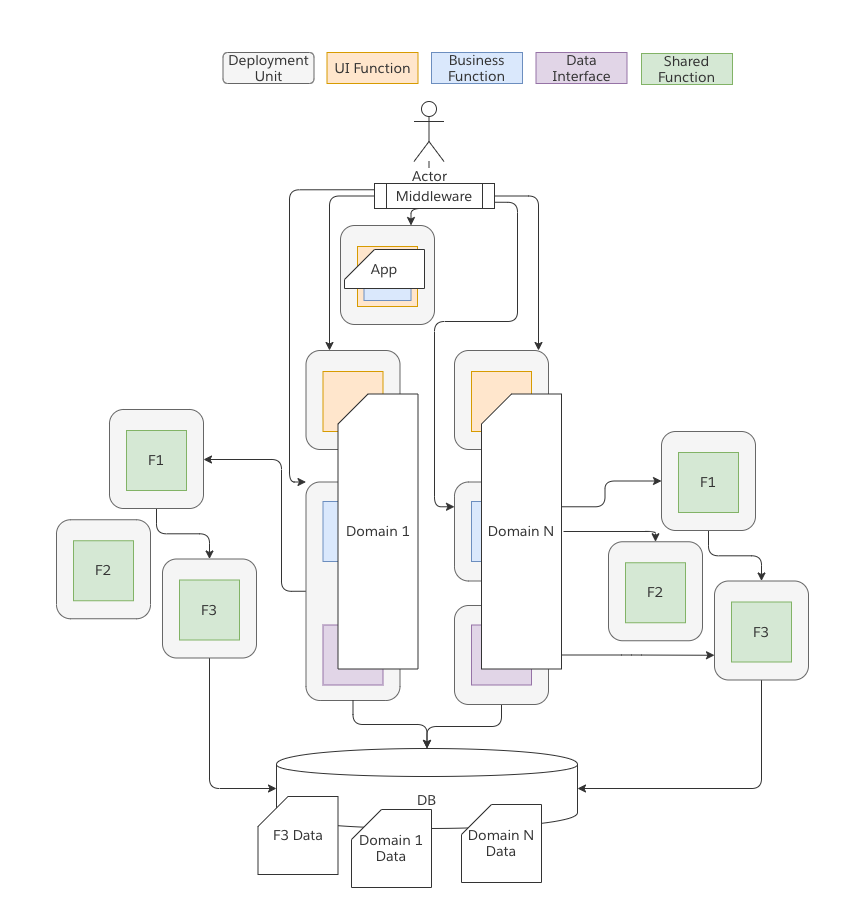

Distributed Monolith

Distributed Monoliths are just evil in my opinion. I say this because such systems incur a high cost with little benefit. There are 2 main areas where Distributed Systems become monoliths.

- Data Monoliths

- Application Monoliths

Data Monoliths are what this image depicts. In effect you separate out a lot of the business logic but maintain a single data store. Ultimately any domain can sneak around an interface boundary and interact with the underlying information that has been stored. This is dangerous and makes such systems extremely difficult to reason about. While some may attempt to argue that there is good reason to do this such as separating out a specific function that requires additional scale I have always observed that it is cleaner to simply make a “copy” of the data required rather then allowing shared access to the same DB.

Application Monoliths exist when the processes used to develop software are the same processes used when a team was building a Monolith. In other words, we may decide that all deployable units must be verified together and only versions fully verified as a “single” unit should be valid in production and this may span our deployment pipelines and release management practices. It may also be that for testing all teams must independently deploy their own full set of deployable units in order to test. It may also be the case that we create feature toggles that attempt to modify behavior across multiple deployed units concurrently. All of these are smells that we are treating our distributed components as a monolith.

The end result with Distributed Monoliths are that we pay a heavy cost to manage a large set of deployments but do not get the agility, singular responsibility, blast radius protections, and more as each team that owns a deployable must orchestrate with all other teams.

Microservices

Microservices originated with the notion of “shared nothing”. For purposes of our description we presume there is no shared process space and no shared data space. Because of PaaS technologies such as K8 I stop here because we call many architectures “Microservices” even though they may not share memory space, CPU, Network, Ingress Processes, Egress Processes, and more. The advantages of Microservices come from the independence that they afford teams through the creation of strong boundaries. When coupled with practices such as Semantic Versioning of APIs, SDLC practices including backwards compatible deployments, and more such systems can allow for smaller and more predictable deployments which have been shown to improve availability, predictability, and more.

The implications and sweet spot

What is interesting to me about breaking things down in this way is how we can make clear the importance of different aspects to the system(s) we are building. For example, if we can solve for modules that are independently testable but happen to be deployed via the same release mechanism as an existing monolith then are micro-services the only alternative to the “monolith” or are there other architectures worth pursuing? How important is the full shared nothing architecture? For example, as K8 schedulers are becoming more complicated I wonder where the real distinction between a JVM thread scheduler and K8 scheduler may ultimately land? How much complexity will we aim to push on developers to understand how to layout their software as compared to when should developers simply be asked to manage their own “executor service” within some larger shared context?

This question is becoming more important to me as I see teams leveraging higher and higher PaaS abstractions (Function as a Service, K8, etc). What I find fascinating is that some of the previous notions that I held important around shared nothing (no shared CPU, memory, etc) are being placed into bin packing and scheduling algorithms (things that Operating Systems have done for a long time). As machines become larger and larger (more CPU power, memory, nvme, etc) - I wonder if we are at a point where the flexibility of distributed systems is as powerful as it once was. It seems to me that as K8 for example becomes more popular that perhaps shared nothing isn’t quite as important as it was before compared to defined interfaces. And in languages like Java where interfaces are perhaps more enforceable the overhead of having to deal with additional layers of complexity may not be worth the effort.

I don’t have any quick solutions with this post but it is something I am keeping an open mind about. Approaches in computer science seem to cycle between more monolithic architectures to distributed - back and forth. I am interested to see just how far K8 starts to look like an OS in the next few years.

Finally, I am not yet sure if I got the degrees of freedom right just yet as documented - if readers feel that there are other important bounds (axis) to consider comment back as I continue to iterate on this notion myself.

Tags: